Don’t wait to do something: Sam Bennett’s dark, personal road to Augusta National

MADISONVILLE, Texas – In the family’s darkest moment, here was one final flicker of light.

Having awoken from an afternoon nap, Mark Bennett was wandering around the house, as he often did, when he bumped into his son, Sam. It was June 2020. Seven years earlier Mark had been diagnosed, at age 45, with early-onset Alzheimer’s, a cruel and unrelenting disease that would eventually rob the gifted dentist of his coordination, reduce him to nightly medical care and transform doting family members into complete strangers. Mark’s deteriorating condition had tested a grieving family in every conceivable way: their patience, their resolve, their faith, even their sanity. But this was a clear-eyed thought from a cloudy mind, and so it was one worth savoring.

Mark squared up his youngest son in the kitchen and told him: “Hey, don’t wait to do something.”

Then patted him on the back.

Sam stood in stunned silence. So did his mother, Stacy.

“Mom,” Sam finally said, “do you think you could get him to write that down?”

And so Stacy grabbed a sheet of paper and sat at the table with her husband of 27 years. A language-arts teacher at the local junior high, she carefully drew each letter, then watched for 15 minutes as Mark tried like hell to recreate them, his face determined, his pencil trembling.

D O N ‘ T

W A I T

T O

D O

S O M E T H I N G

Then he signed the message, “Pops”, in what looked like pre-K scribble.

Sam folded the paper and stashed it in his truck. Eventually, he knew what to do with it, how to memorialize it. But for now, it was simply a cherished memento.

The last thing his father ever wrote.

* * *

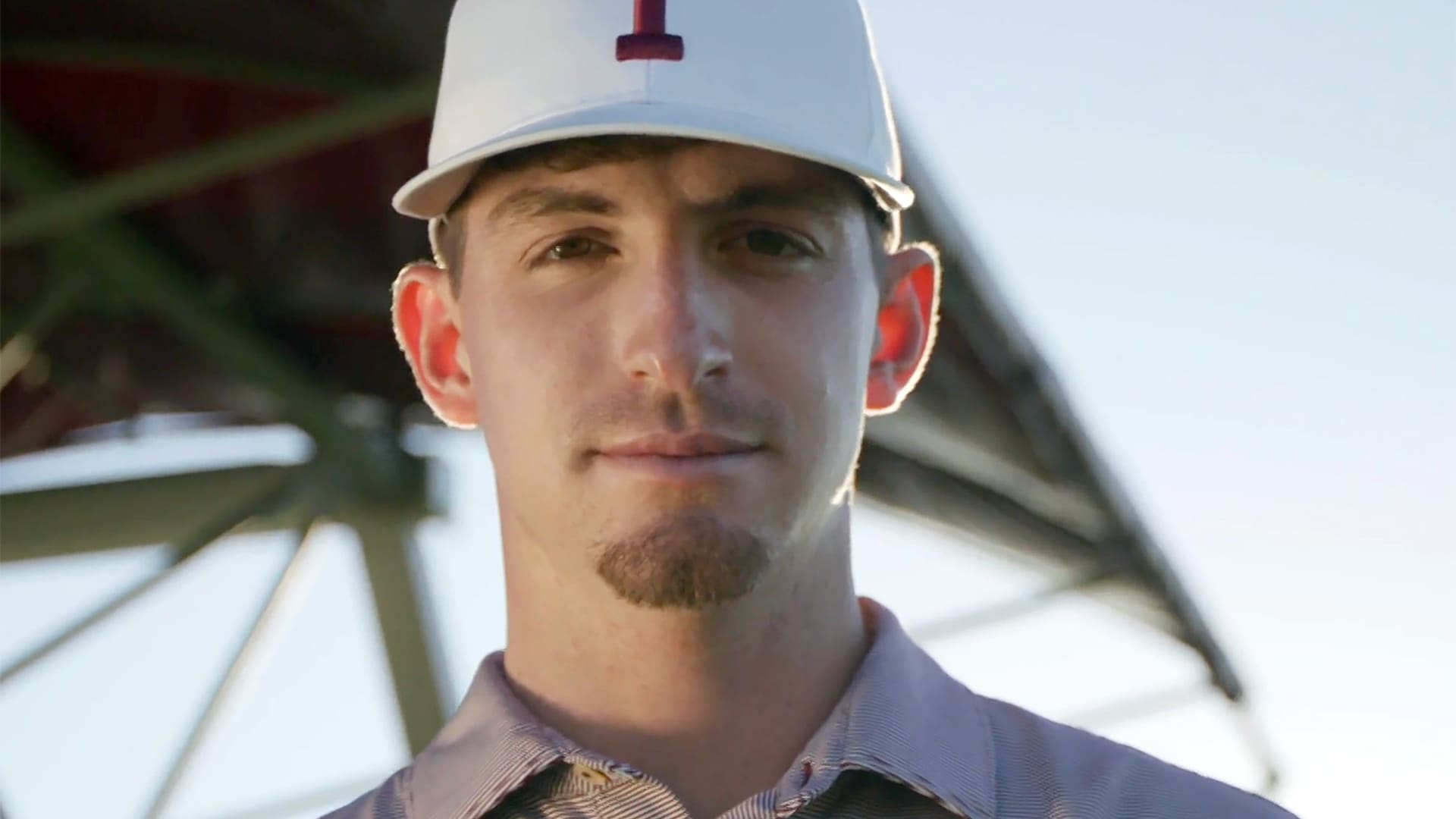

MADISONVILLE IS HOME TO Buc-ee’s, two stoplights and roughly 4,500 residents, including the famously tattooed U.S. Amateur champion.

Located in southeast Texas, nearly smack dab between Houston and Dallas, Madisonville has been home to the Bennett clan for generations. Mark and Stacy were born there. Their parents still live there; even at 82, Mark’s father, Butch, practices at the family dentistry, while Mark’s cousin owns an attorney’s office downtown.

“It’s heaven on earth,” Stacy says. Friday night lights. Authentic Mexican joints. Packed churches. “It’s a great place to live.”

Mark and Stacy met in the chocolate milk line in kindergarten and were inseparable throughout high school. They married in 1993 and raised three boys, separated by five years.

“He was my best friend,” says Stacy, 56. “When people say they’ve ‘met their person’ or whatever, that’s not a trite saying – because he was. I can honestly say we never spent a night alone or in anger. He bragged on me. I’ve worn my hair 15,000 ways, and I promise you, I’ve shaved it three times completely, and he goes, ‘God, you’re just beautiful.’ He was always like that.”

Growing up, Mark was the prototypical hands-on father, never missing a game, whipping the boys around Stanmire Lake, teaching them how to duck hunt, fish and play golf. Little Sammy proved a quick study: With ESPN or Golf Channel blaring in the living room, he’d stand there in his pull-ups, studying the swings of the players on TV. Then he’d head into the family’s two-acre yard, single out a tree and bet his mom a quarter that he’d nail it on the fly. His piggy bank filled up quickly.

A slightly more formal education was offered a mile away, at nine-hole Oak Ridge, the kind of basic muni with sputtering Yamaha carts, an algae-filled pool and a welcome sign promoting sponsors like B. Dale Septic Services and Donkey Dumpster Rentals. With a homemade action on a homely track, Sam’s sole focus was surviving fierce battles with his older brothers, Marcus and Jake.

“He was always an athlete,” Stacy says. “He had a gift of meekness, but also a gift of power at the same time. You know how everybody roots for the little guy? Sam was always the little guy. Everybody just adopted him. There wasn’t too much he couldn’t do.”

Undersized and overlooked in four varsity sports, Sam grew accustomed to carrying a sizable chip on his slender shoulders. He was the gritty shortstop darting across the diamond like a fire ant. He was the indefatigable tennis player making his opponent sweat every point. As a freshman on the varsity basketball team, he’d routinely get mocked when he was introduced as part of the starting five, his jersey dripping off his slight frame. “It took everything I had not to go whip somebody myself,” Stacy says, “but I just wanted to say, Uh-huh, y’all just see in a minute.” And sure enough, from the opening tip, Bennett would play suffocating defense and bury 3s, swaggering back down the court. “That shut them up real quick,” she says.

Bennett was similarly feisty on the course. After pure strikes, he’d chirp and theatrically spin his clubs like a baton twirler. Texas A&M coach Brian Kortan recruited Bennett for the first time at a junior tournament in College Station, where he played in a walking boot and carried a bag so big it clanked off his calves.

“He was never the biggest guy in the room, never the fastest guy in the room,” Kortan says. “But, man, I don’t know if there’s anybody in that room that could compete with that guy.”

When Sam was 13, Mark upgraded to a membership at the Traditions Club, A&M’s home course about 45 minutes away, betting that his youngest son could earn a college scholarship with the proper training. Playing on better courses against stiffer competition, and growing into his 5-foot-10-inch, 145-pound frame, Bennett’s name rocketed up the junior rankings.

In the end, his college decision wasn’t much of a choice at all. He signed with A&M, the same school his father had attended in the mid-1980s.

“I’m a small-town kid, and I’ll always be that,” Sam says, “and College Station gives me that vibe as well.”

But deep down, there was another reason: “I love my family. I didn’t want to be far.”

Especially with his home life slowly unraveling.

* * *

THE SIGNS ARRIVED SPORADICALLY, then all at once.

At work, Mark began misplacing his keys and dental instruments. He struggled to recall times and places and plans. Forgetfulness is an accepted part of aging – but not like this. Not at 43. Not when he drew blanks on longtime friends’ names. Not when routine drives became misadventures.

At first, doctors said Mark had mild cognitive impairment – an official name for his increasingly frequent memory lapses. But after a while, growing more concerned, he opted for more tests. Two years later, Mark was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s, a progressive and incurable disease that, per Nantz National Center research, affects a “fraction of 1%” of men that age.

“I was mad at God,” Stacy says. “Mark was the epitome of perfection, and so I went down that unfair road. God always answers prayers. He knows better. And sometimes His answer is no. I asked Him, and He told me no.”

Sam was midway through high school, about to display his game on a national stage, when the stressors started piling up. Sometimes, he was withdrawn. Occasionally, he was angry, raging at the idea that his seemingly healthy father was being wronged. But mostly, he just compartmentalized his sorrow, stuffing his heartbreak somewhere deep inside and pouring himself into his golf.

A&M became Sam’s getaway, made even safer by the presence of Kortan, who had experience in losing a parent at an early age. Kortan was 25 when his own father succumbed to lung cancer, and his trials in dealing with grief, while also chasing his tour card, resonated with Bennett.

“When he finally did come around to telling us, I don’t think he understood the severity of the prognosis. Or maybe he didn’t want to,” Kortan says. “But we just constantly talked to him about how this is the place where you can be you, and you can put everything else away and do what you like to do. And then when we’re off the golf course, we’ll fight the battles that we have to fight on a daily basis.”

After two steady seasons for the Aggies, Bennett soared during his junior year, earning first-team All-America honors and posting the second-lowest scoring average in school history. Even now, it seems unfathomable that a player could summon the best golf of his life while less than an hour away, in his childhood home, his father – his hero – was withering away in a hospital bed, the light inside becoming dimmer.

“It’s his competitiveness,” Kortan says. “He didn’t want to be seen as somebody that couldn’t overcome what had gone down. He wasn’t gonna fail. He wasn’t gonna let his family down.”

But that burden finally threatened to overwhelm Bennett in spring 2021. That March, he claimed his first college title, which also secured him an invite later that month into the PGA Tour’s Valero Texas Open. It should have been one of the most satisfying moments of his career, hard-earned validation, but instead it served as a sad reminder of all he’d lost. Mark had stopped traveling during Sam’s sophomore year, and by that point in his decline, he had no concept of what his son had accomplished.

“Not getting to physically be with Sam and see Sam play his best golf ever,” Stacy says, “yeah, that bothers me an awful lot.”

And it affected Sam more than he let on, too. For years he had tried to play for more than himself, to uplift his parents, to give them one less thing to worry about. “He just wanted to protect us,” Stacy says, “and let us know that if he’s OK, then we should all be OK.” But Sam wasn’t OK. He felt guilty that he wasn’t around more. Guilty that his dad had to go instead of him. Guilty that he didn’t have a steady relationship like his brothers. Wracked with anxiety and depression, he’d call Kortan at 5 a.m., unable to sleep, his mind racing. At night he’d pace around town.

“I couldn’t take it anymore,” he says. “I felt like I was about to crawl outta my skin. I was struggling. I couldn’t really function. It was affecting my everyday life.”

Sam returned to Madisonville less and less frequently, his father’s dementia worsening, the final few months too chaotic, the light all but gone. With Sam away at school, his brothers picked up the slack at home. Jake, 26, served as Mark’s primary caregiver during the final year, his days filled with diaper changes and feedings and park visits, little acts to stimulate a decaying mind. Marcus, 28, often jetted over in the middle of the night when the nurses couldn’t soothe “Doc” or coax him into the bathtub or change his sheets.

The around-the-clock care allowed Stacy to continue to work, but nighttime was even more upsetting. For the first time, they were sleeping separately: Stacy in the bedroom, eyes pressed shut, hoping for enough rest to function the next day; Mark in a nearby room, flanked by nurses, up all night.

“It’s like being in the bottom of a pit and knowing that the hand of God was coming down somewhere, but you couldn’t see it right then. That was the hardest part,” Stacy says.

“And not knowing who we were at the end …”

She remembers.

She remembers they were in the house one day, the house they moved into Thanksgiving 1999, the house where they stayed up late grilling hamburgers and shooting hoops, the house where they’d laughed and loved, where they’d grown and grieved, where they’d celebrated engagements and welcomed babies … and Mark stared at his wife of more than a quarter-century, scrunched his face and asked: “Now, who are you again?”

“I turned away and I went outside and bawled my eyes out. I cried and cried and cried,” Stacy says. “I kept telling myself, somewhere deep inside of him, he knows who you are – he just can’t verbalize it. That blank stare. It’s the hardest thing I have ever gone through.”

Comfort arrived in ways big and small, in the tight-knit town she’s always called home. There were house calls and hugs downtown. Students hung hundreds of heartfelt notes on the Tree of Happiness behind her desk. And with the end nearing that spring, after the school’s morning announcements, her first-period class would form a prayer circle, place their hands on her and bow their heads. Her eyes wet with tears, Stacy would clear her throat and begin another long day.

* * *

“MY DAD WOULDN’T WANT me to cuss up here, but these past seven months have effing sucked.”

That’s how Sam began his father’s celebration of life on June 15, 2021, in such a packed First United Methodist Church in Madisonville that they had to offer overflow seating.

The “baby” of the bunch, Sam spoke last, for three minutes, rocking back and forth while lamenting how the Bennett boys were “peaking right now” – new jobs, marriage, Tour starts – and yet their dad couldn’t share in their successes.

“You know,” Sam said, “that’s tough.”

The day after his father died, Sam flew to Illinois to join his U.S. teammates at the Palmer Cup. In a preview on the A&M website, there was nary a mention of the fresh trauma in Sam’s personal life – only how the selection for the elite team was “an exclamation point on a great year.”

“Golf was his escape room,” Stacy says. “He could just get out there and lose himself. He knew, if he was living out the dream that he had as a small child, that he could just stay the course and go forward and that it would be OK with everybody.”

For Stacy, those first few months were a blur, her emotions all over the place. She added a third tattoo (the infinity sign, with the message, “Until we meet again”) to preserve Mark’s memory, but then again, how could she forget? Each morning she awakened in the single-story, brick house they built, in the bedroom they shared, to nothing but echoes and memories. With friends and family, she laughed and cried. Joked and grieved. Stayed up and slept in. It was all so wonderful and miserable.

“We were so blessed to have him,” Stacy says. “There’s people in this world that will absolutely never be loved like that in their whole lifetime. I wouldn’t trade it. Nuh-uh, even if I knew the outcome and I could trade it, I wouldn’t trade it for anything in the world.”

Back on campus, Kortan relived his own traumatic moments. When his father died, one of the most helpful bits of advice was that there was no need to rush the grieving process. There was no set timeline. And so for the first few months, he and Sam would go to lunch, hit balls, talk for hours in his office. He’d hold Sam accountable, but also give him freedom. He reminded Sam that he was ready, that his dad had prepared him for life, that he was going to be OK – even if it didn’t always register.

“I don’t know what the shelf life for grieving is,” Kortan says. “But the maturation process really came down to him understanding that he could do this without his dad. That he still had more to give, more that he wanted to do himself.”

But it wasn’t just Kortan who helped start the healing process. Since late 2020 Bennett had been taking antidepressants and meeting weekly with an on-campus sports psychologist to deal with his anxious thoughts.

“I was tired of feeling that way, and I knew that I wanted to live a happy life,” Bennett says. Those sessions helped him develop a daily routine to calm his overactive mind, channel his nervous energy and process his new reality. “I know he’s not sick anymore and not struggling. That gives me peace.”

During his senior season, Bennett once again was named to the first-team All-America squad and became a Player of the Year finalist. Because of his consistently excellent play, he was ranked inside the top 5 in the PGA Tour University standings, ticketing him for full status on the Korn Ferry Tour after the college season. But a month before nationals, Bennett announced that he was forfeiting the KFT card and returning to A&M for a fifth year. He raised even more eyebrows by competing only sparingly in the summer.

Publicly, he said that he needed more time to improve physically and recover mentally.

But he was also gearing up for a final run at the U.S. Amateur.

* * *

NEVER IN BENNETT’S ATHLETIC career has he lacked motivation. The runt of the family versus the big brothers. The small-town kid against the country-clubbers. The scrawny freshman taking on the upperclassmen. His Texas twang, his chin patch, his OB-stake limbs, his unorthodox swing – “people just talk crap,” he says.

And, sometimes, apparently, they don’t talk enough.

Bennett entered the 2022 U.S. Amateur as the third-ranked player in the world, fresh off a tie for 49th at the U.S. Open, and yet he didn’t see his name listed anywhere on a pre-tournament post of the top-10 favorites, didn’t hear his name being mentioned in preview videos, didn’t feel the respect on the range. That familiar feeling was bubbling up inside.

“He likes to think that he’s not getting the recognition he deserves,” Kortan says, “because I think it fires him up. In his heart, he likes being the underdog. I hadn’t seen him that locked in, ever.”

Before the tournament, Bennett asked his family to stay home in Madisonville, so he could fully focus. He needed one last go-round with Kortan, just the two of them, and he entrusted him with every yardage, shot shape and trajectory. With its narrow fairways and punishing rough, Ridgewood Country Club played right into Bennett’s strengths – and he knew it. On the eve of the tournament, Bennett told Kortan that if he could just get through qualifying, he’d win. But after nabbing the 36th seed, his two-round total put him on the same side of the knockout bracket as some of the biggest names in the amateur game: Nick Gabrelcik, Fred Biondi, David Puig, Stewart Hagestad, Dylan Menante. Their average world ranking: 13.6.

And yet, with one savage club twirl after another, Bennett mowed each of them down, even woofing after his quarterfinal win: “I feel like I’m the dog in this race right now.”

Staked to a 1-up lead in the semifinals, moments from victory, Bennett gathered himself on the final green and glanced down at his left forearm.

At his tattoo.

DON’T WAIT TO DO SOMETHING.

After his dad had mustered the strength to scratch out that message, Bennett stored the note in the center console of his Chevy Silverado. The next month, following a tournament practice round in Dallas, Bennett stumbled into a tattoo shop and asked the artist: “Hey, can I get this tatted on me?” Forty-five minutes later, Mark’s memory was preserved in ink.

Bennett’s chest and ribs were already covered in tattoos – five birds for his family members, the Methodist cross for his faith – and now he had his dying father’s labored script to signify what Sam has overcome, what truly matters to him, and what’s still possible.

That mantra has guided Bennett through some of the toughest times of his young life. For a while, it was part of his pre-shot routine – a reminder to play boldly, and that his biggest fan was always rooting him on. But it was also how he ended his father’s eulogy back in Madisonville. It was why he bravely took the step to address his mental health challenges. It has informed, in some way, every decision he has made since: his play, his outlook, his relationships, his future. It speaks to the power of faith, of being intentional. It’s why he could stand there, on national TV, and boast that he’s “the dog” left in the race.

“For the longest time, I’ve lived my life in fear just seeing what my dad went through,” Sam says. “So, to me, it means just don’t be scared of anything you do.”

And now he was two putts away from playing for the highest honor in amateur golf, from locking up two major exemptions, from golf immortality.

He looked down. Smiled. Then refocused.

“Don’t wait to do something,” he told himself.

“Just one more time …

“Just one more time …”

* * *

IT’S A WARM SPRING day in College Station, and Bennett is carrying the Havemeyer Trophy through the locker room at the Traditions Club. He didn’t just two-putt the final green at Ridgewood to clinch a spot in the championship match; the next day, in the 36-hole final against Ben Carr, Bennett earned a narrow victory to claim amateur golf’s biggest prize.

When it was over, Bennett and Carr both glanced skyward. In a fateful twist, both U.S. Amateur finalists had lost their fathers in recent years, and this time, it was Bennett who offered solace to his opponent: “I know his family and his dad are super proud.” Bennett’s own winning reaction was so tempered that Kortan actually had to remind him, Dude, you just won the U.S. Amateur.

“I cried a little bit,” Sam says, “because I was thinking about my dad and wishing he could be there.”

The 23-year-old stands at an uncomfortable juncture, asked repeatedly to reflect on his painful past while also preparing for a limitless future, his tragedy and talent forever intertwined. This week he’s playing in the Masters, with Kortan again on the bag. In a few weeks he’ll chase an SEC ring alongside his A&M teammates. And next month, after he makes good on his promise to graduate, he’ll begin his final pursuit of an NCAA title.

Once again, after nationals, Bennett is on track for a Korn Ferry Tour card – and this time, he says, he’s ready to accept it. He’s as physically prepared as possible, having already appeared in pro events. And now he possesses the mental tools to handle any anxious flareups or dark thoughts. It’s still surreal to him that folks will slide into his Instagram DMs and thank him for sharing his struggles, for being an inspiration.

“It might suck at the time, but it isn’t how it’s going to be forever – it does eventually get better,” he says. “This is probably the best mentally I’ve been in a while. This is right where I want to be.”

But as much as his life is about to dramatically change, so much will remain the same. He plans to stay in College Station, in his safe place, keeping close to Kortan, to his friends and family, to Madisonville.

Back home, Stacy Bennett beams with pride as little Sammy has become a local legend. From Walker’s Cafe to the hair studio to the county courthouse, everyone is quick with a connection or story, reminders of his greatness all over town. The marquee at Standley Feed & Seed salutes their national champion. A small shrine has been erected at the old muni down the street. And the walls in Mark Bennett’s dental office are adorned with his youngest son’s newspaper clips and trophy shots, a tribute to the resilient family hero.

“I used to be Mark’s wife,” Stacy says, “and everywhere I go now, I’m Sam’s mom.

“I’ll take that title.”